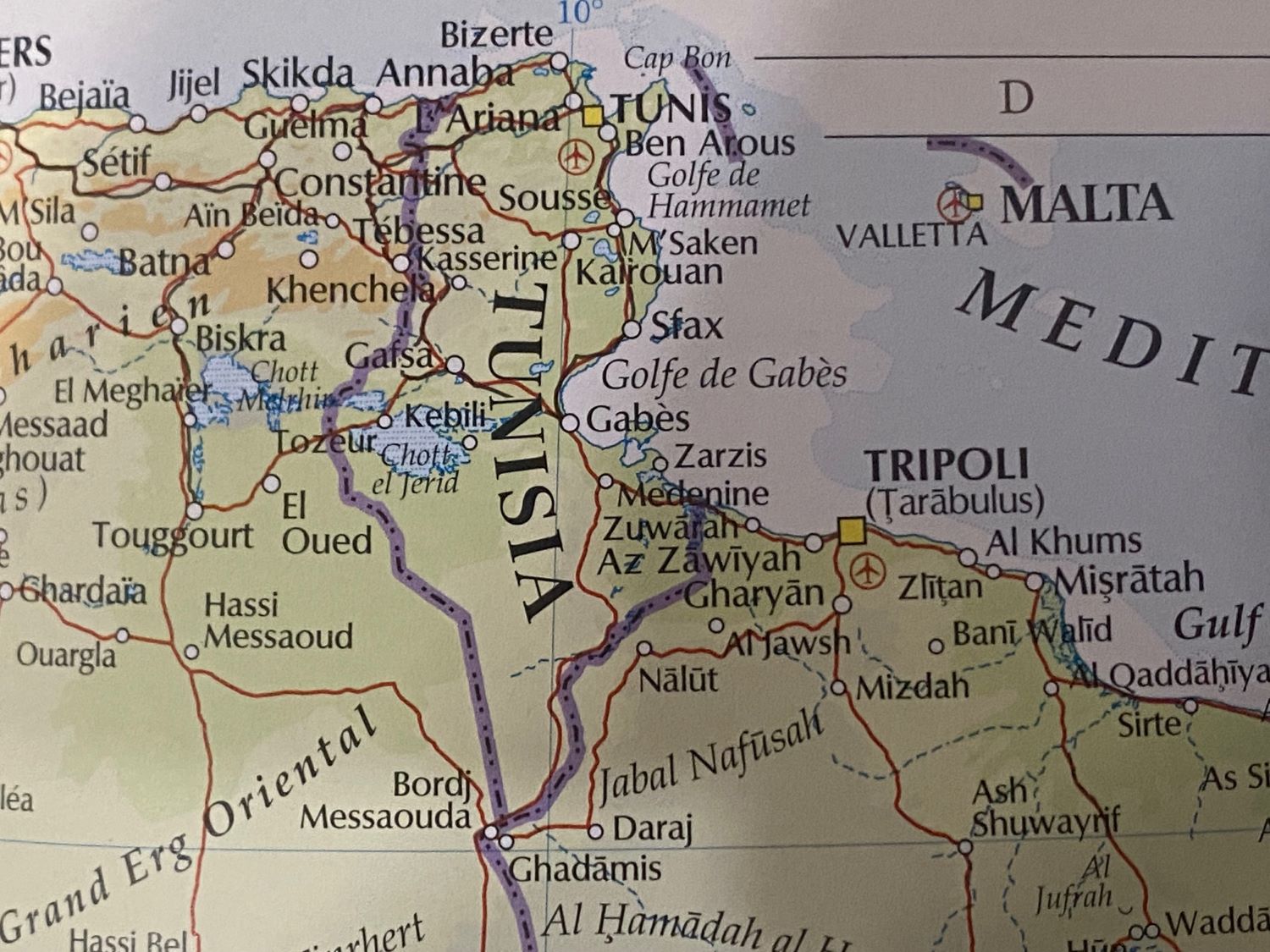

It was the late eighties. My girlfriend and I took a couple of weeks off from our jobs in Germany to explore parts of northern Tunisia, selecting a hotel on the beach about an hour’s drive from the capital, Tunis.

The beaches were scattered with colourful boats and umbrellas; the water was pristine, clear like glass, and warm. The town was appealing to the eye – white stone houses, strikingly contrasted with indigo framed windows and solid indigo doors. Palm trees provided respite from the burning sun. All seemed like paradise.

After a couple of beach days, we walked to the local market, where vendors sold their wares from small stores, their goods spilling out onto the street in brilliant displays. Those who didn’t have a permanent shop sold items from tables under temporary canopies in the courtyards. None of the products had price tags attached. Some of the streets in the market were quite narrow, with people crowding in on one another, and my girlfriend would sometimes feel the touch of a wandering hand.

Inevitably, a young boy insisted on showing us around. We declined, but he followed us anyway, trying to coax us into various shops, most of which we rejected. A shop selling traditional hand-painted plates showed promise, so we entered.

While my girlfriend was looking at the plates, the boy coaxed me outside. He wanted to show me something. He motioned that he wanted me to come further out into the courtyard, but I didn’t want to wander too far. I thought nothing was unusual when the boy slipped behind me as he was gesturing about something. Then I heard my girlfriend yelling for help.

I turned to run back inside, but the boy was blocking the entrance. His eyes were wide – fear perhaps – and he held his hands in front of him, pleading as he tried to prevent me from entering. No, no, it is okay. No problem. It is okay.

My girlfriend continued calling.

I pushed the boy aside roughly and stepped into the shop. The strong young proprietor had my girlfriend pinned against a table, one hand on her breast, the other up inside her skirt, groping, while she tried to fight him off.

I blazed with anger. Perhaps I hadn’t really believed in the concept of temporary insanity before, but I do now. I was completely, utterly, thoroughly out of my mind. Tear down the walls! Smash the plates! Cut the man to ribbons with the shards!

The man saw me fast approaching and released my girlfriend. Hands waved wildly in front of him; he had real fear in his eyes. I was about to kill him, after all, and he knew it. No, no, it is okay, no problem, just a misunderstanding! He stepped as far back as he could, his back against a table, hands still waving frantically.

But somehow, in the five strides it took me to cross the room, I regained my sanity. Had the room taken only three steps to cross, there may have been a completely different outcome. As it was, I checked my aggression, grabbed my now tearful girlfriend by the hand and walked out.

The boy followed, but I told him to piss off. He pleaded that it was okay, just a misunderstanding, but I wouldn’t have any of it. He was persistent though, following us all the way back to our hotel, arguing that he should at least be rewarded for the work he had done to show us the market. I was still furious, indeed would continue being incensed all through the night and into the next day. I gave the boy nothing.

My girlfriend and I reflected on the event the next day. Was it the clothes she was wearing – blouse and a skirt – that showed too much skin? Were they inappropriate for this culture? We weren’t sure, but there were many other female tourists in the market dressed similarly. Besides, she didn’t have anything else to wear; we would have to buy more clothes if this was the case.

Was it her blonde hair and blue eyes, unusual and perhaps exotic to Tunisian men? Maybe, since there weren’t many with her look around the area. Had we done anything wrong that would have solicited such behaviour? We couldn’t think of anything.

Was it possible we were unlucky enough to come across a man, maybe even a good man who loved and cared for his family, but who had displayed particularly bad behaviour in this instance? The event was discouraging and frightening enough that, initially, we planned to just stay at the hotel for the duration of our trip. But there was so much to see and we didn’t want to succumb to fear.

We booked a tour to Tunis in our second week. In addition to agreeing that we wouldn’t get separated again, we agreed that we wouldn’t go inside any shops. We would stick to the street stalls in Tunis. Part of the tour included a camel ride, but the tour guide explained that we would actually be riding dromedaries. With a straight face, he clarified that a dromedary has one hump and four legs, and a camel has two humps and six legs. In the bus, the passengers all glanced at one another. Did he just say six legs? But then the tour guide laughed. Ah, a joke. We all laughed too.

At the Tunis market, we stayed with the outdoor stalls, which were positioned further apart in comparison to the market we had visited the week prior, making it easy to avoid wandering hands. It was still noisy, however, with everyone seemingly yelling at once, calling attention to their products.

Again, there were no price tags on any of the items. One was required to haggle for the best price. I’m not one who usually buys kitsch, but I admired a handmade keychain. After the vendor started at an initial price of 40 dinars (about CAD $20), I managed to talk him down to one dinar. I began to walk away when he said he wouldn’t let it go for less than two, but then he followed me through the market a little way before ceding. He took my money and gestured to the heavens; hands clasped tightly. His poor family. How would he feed his family with these kinds of sales?

I actually felt sorry for him. I was new to haggling and I had no way of knowing if he was seriously upset and worrying, or if it was just for show to get a better price.

My girlfriend negotiated well, talking a vendor down from 120 dinars to ten for a handbag. He, too, suffered dramatically before taking her money. Please, please, more money, I have a family to feed!

My goodness, were we really ripping these people off? I doubted it. After all, that’s what haggling leads to – either an agreed price or no sale at all. I doubted vendors would be selling below cost.

Later, I felt better about the whole thing when we found a department store outside the street market, in which all the products were marked with price tags. Wandering through the aisles, we came across a duplicate of the handbag my girlfriend had just purchased in the market. The price was listed as ten dinars, exactly the price she negotiated with the vendor. Freaky.

We didn’t experience any disrespectful incidents in Tunis. Yes, vendors were aggressive and boys followed us everywhere looking for handouts, but our faith in the people of the country had been restored. We had just been unlucky with a man displaying bad behaviour.

It’s true that sometimes just one rotten apple can taint the rest of the fruit in the basket, but we felt the people of Tunisia were like any others, generally good and helpful. We felt our Tunisian adventure had been worthwhile and educational.

Back in Germany, I related my girlfriend’s story to a coworker. He said that when he and his girlfriend – also a blonde with blue eyes – were in a Tunisian market a year prior, a man had snuck up behind her, quickly yanked on her long hair, and snipped a large handful with scissors. My coworker initially started chasing him, but the offender had swiftly disappeared into the crowd. That incident happened on their first day in Tunisia and they never left their hotel afterward for the rest of their trip.